Microbes key to stopping the next pandemic

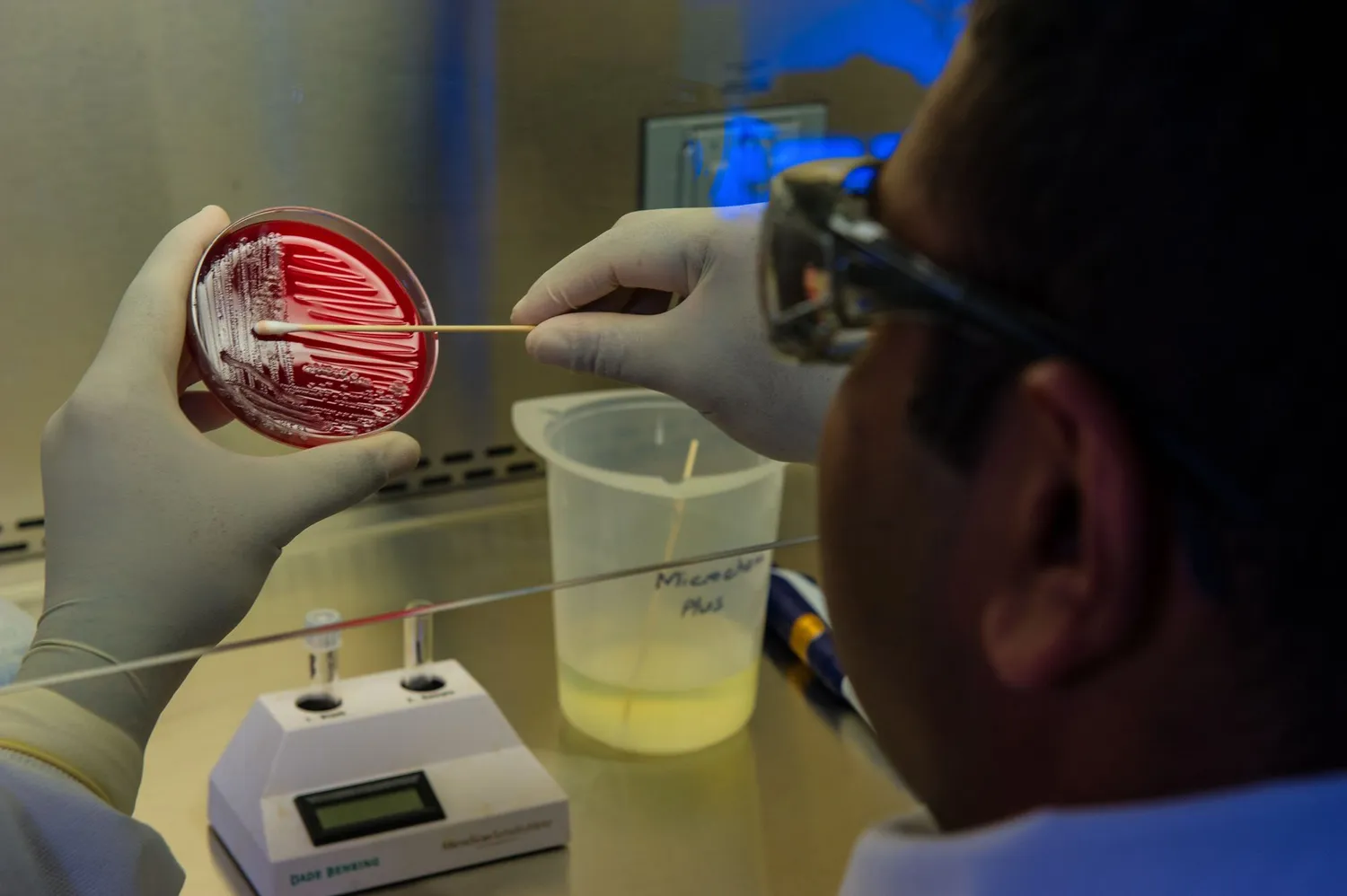

Preventing future pandemics depends on better understanding of the billions of microbes circulating all around us in nature. Most microbes are harmless and can even be symbiotically or mutually beneficial. However, a transmissible, cross-species virus such as COVID-19, can also hypothetically kill hundreds of millions of people. When a new pathogen circulates the opportunity to respond is often a matter of weeks. If it takes too long, leaders face a choice: save lives or save your economy. “We are still stuck in a 20th century mode of finding a pathogen, developing a vaccine and waiting for the next pathogen,” says Dennis Carroll, former director of the US Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Pandemic Influenza and Other Emerging Threats Unit.

Understanding how microbes swap genes and work together in cross-species networks known as microbiomes, is where things stand to get especially interesting. Microbes have thrived for almost four billion years and can survive extreme environments ranging from boiling hydrothermal vents in the deep oceans to the International Space Station! The potential benefits of solving the genetic secrets of microbes surpass pandemic prevention. Microbiology is central to all the grand societal challenges that lie ahead, such as food security, biological weapons, ocean health and climate change etc. In our oceans in the Arctic and Amazon region, marine microbiomes recycle greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane. However, our warming planet may be changing their metabolism and possibly damaging that role.

In the last century we have made greta progress in our ability to read, edit and redesign the genetic source code of cells and biological systems. Run a random teaspoon of seawater through a sequencer and you’ll find gigabytes of genetic information, some of which could result in new food biotechnology applications and biomaterials. There are an estimated 10 nonillion (or 10 followed by 30 zeros) individual viruses, well more than all the stars in the observable universe and an estimated 5 million, trillion, trillion bacteria.

Whatever choices we make, the microbial world will continue to send us signals. SARS, avian flu, swine flu, Ebola, Zika and monkeypox all suggest enhanced disease spillover risks as the expanding world population continues to invade the natural environment. An abundance of antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiparasitics into nature has triggered adaptations that make various infections harder to treat. People and microbe fates are intertwined and the microbes are in it for the long haul!

Reference:

Bremner, B. (2022). Man Versus Microbe. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1142/q0329